One of the best ways to discover the perfect source for your topic is to browse the library stacks by call number range. Each call number range represents a particular subject and all of the books on a particular topic will be located in the same general area on the shelves. So if you want a book on Latin American literature, go to the call number range beginning with PQ7081 to see what we have!

Welcome to the research guide for SPAN 405: Critical Methods!

Please reach out at any point in time if you need assistance with research! Schedule an appointment here.

Tori Golden, tgolden2@luc.edu

Critical methods means the different ways scholars analyze, interpret, and research works of Spanish literature. Instead of just asking what happens in a text, critical methods ask how we can understand it through different perspectives.

Theoretical approaches: Critics might look at a novel or poem through the lens of history, gender, politics, or psychoanalysis. For example, a Marxist critic might focus on class struggle in Lorca’s plays, while a feminist critic might examine how Carmen Laforet portrays women’s roles in Nada.

Research strategies: Scholars use advanced tools to locate and analyze texts—such as specialized databases (MLA International Bibliography, Dialnet), digital archives (Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes), or rare book collections. They also track how other scholars have debated and interpreted the same works over time.

Why it matters: Critical methods help you enter scholarly conversations, develop original arguments, and situate your own interpretations within broader debates about Spanish literature.

In other words, critical methods give you both the lenses to read literature more deeply and the research practices to study it as a scholar.

The library catalog is a great place to start your research. Here are some tips to make searching more effective:

How is exile represented in post-Civil War Spanish poetry?

Break down your research question into main ideas:

Exile

Spanish Civil War / Postwar Spain

Poetry / Literature

Think across languages (English + Spanish) and disciplinary vocabulary:

Exile: exile, diaspora, banishment / exilio, destierro

Spanish Civil War / Postwar Spain: Spanish Civil War, Franco era, postwar Spain / Guerra Civil Española, franquismo, posguerra

Poetry: poetry, poets, literature / poesía, poetas, literatura

Use Boolean operators (AND, OR) and quotation marks (“ ”) to combine your terms.

Try your searches in different databases (MLA, JSTOR, Dialnet, Cervantes Virtual).

Compare results: Does searching in Spanish give you more literary criticism? Does English yield more historical context?

Look for new keywords or authors’ names in the articles you find and add them to your search.

'Citation Tracing' (also known as 'Citation Tracking') refers to both finding references cited in a given article and finding newer articles that cite the original article.

Think about whether you need to go back in time or forward in time. Ask:

This allows you to follow research-as-a-conversation through time--cited references are past research, while citing works are more recent (relative to the article you already know about.)

Finding Citing Works in Google Scholar

In the Results list of Google Scholar, below the entry for each result that has been cited, will be a 'Cited by [number]' link. The [number] is how many other entries Google Scholar has found that cite that work. Some of these may be duplicates. Click the link to see a list of citing works.

If there is no 'Cited by' link, then Google Scholar has not found any citing works. That does not mean it hasn't been cited, just that GS doesn't have records.

Note: pay attention to dates. Extremely new articles will have few if any 'Cited by' works, just because no one has had time to publish anything newer. Classic and high impact works may have hundreds (even thousands) of 'Cited by' works.

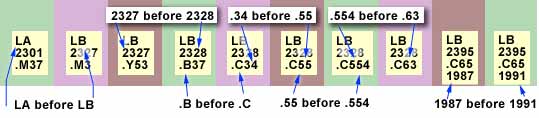

How To Read Call Numbers

This is an explanation of how books with Library of Congress call numbers are sorted. This gives a better understanding of Library of Congress shelving.

Primary sources are the original texts or cultural materials you are studying. These come directly from the time period or author you’re researching.

Examples:

Novels, poems, plays, short stories (Lorca’s Romancero gitano, Laforet’s Nada, Cernuda’s Las nubes)

Letters, diaries, exile journals, manifestos, political speeches

First editions, manuscripts, archival materials

Newspapers, magazines, pamphlets from the Civil War or Franco era

Posters, photographs, performances, film adaptations

Secondary sources are scholarly works that analyze, interpret, or critique primary sources. These put the original works into context or apply a theoretical framework.

Examples:

Peer-reviewed journal articles on Lorca, Cernuda, or Laforet

Book chapters analyzing exile in postwar poetry

Edited collections applying feminist, psychoanalytic, or Marxist criticism to Spanish literature

Biographies or critical companions to Spanish authors

Primary sources = the texts you interpret.

Secondary sources = how other scholars have interpreted those texts.

In your assignments, you’ll usually combine both: analyzing a primary text while engaging with existing scholarship to situate your argument in the critical conversation.